AN AMERICAN ROOK RIFLE

A Version of this Essay Appears in the 2016 Gun Digest

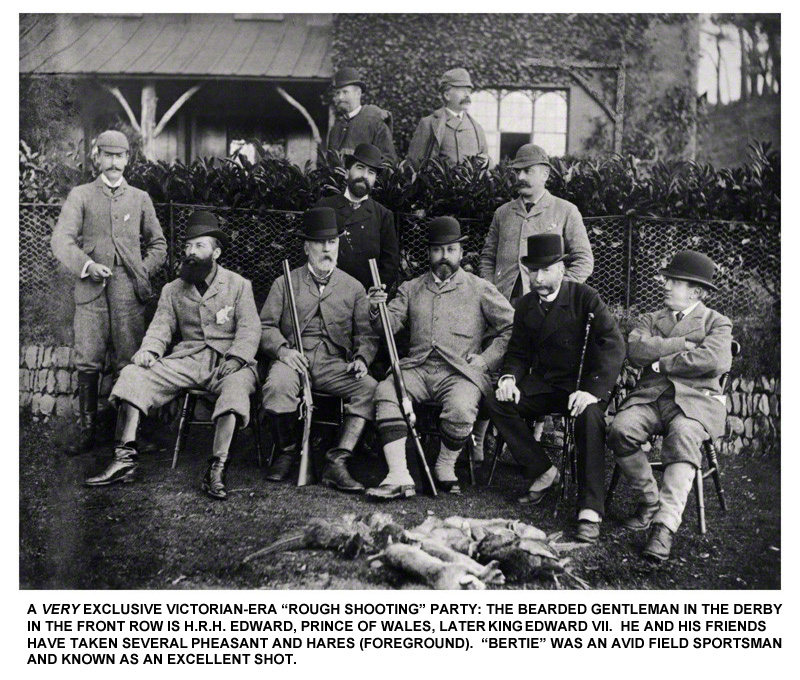

Great Britain’s Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851 was a stunning display of industrial development, demonstrating to the world what Victorian engineers and manufacturers could do: the Industrial Revolution that had begun a century before had made Britain into the world’s trading center, expanding the middle class and transforming an agrarian society into “a nation of shopkeepers” and manufacturers.

In the 19th and early 20th Centuries

the British gun trade was a vibrant industry, serving the world and the needs

of the home market on a large scale. Wealthy people—peers, members of the rural

squirearchy, and barons of industry—sought the delights of the countryside, buying

large estates and taking up traditional country pursuits. Respectable gentlemen

and ladies of Victorian times enjoyed fox hunting, trout fishing, deerstalking,

and  “shoots” for grouse and pheasant, often as part of elaborate country-house

parties. The rich bought finely-wrought

firearms from the greatest names in British gun-making. Their gamekeepers, hired to protect their land

and game, also needed shotguns and rifles to do their work. Many members of the middle classes enjoyed

shooting, if on a less grand scale than “the quality.”

“shoots” for grouse and pheasant, often as part of elaborate country-house

parties. The rich bought finely-wrought

firearms from the greatest names in British gun-making. Their gamekeepers, hired to protect their land

and game, also needed shotguns and rifles to do their work. Many members of the middle classes enjoyed

shooting, if on a less grand scale than “the quality.”

It was also a time of transition in firearms technology, as muzzle-loaders gave way to breech-loaders. Gun designers could work with novel mechanisms and ideas, and along the way produce new types of guns for their clients. Among them was what came to be known as the “rook and rabbit rifle,” a dainty gun perfectly adapted to a gentleman’s recreational “rough shoot” or a gamekeeper’s duty of eliminating pests. The classic rook rifle is a light, small caliber, single shot firearm, made on a break-open, dropping- or falling-block action, almost always in take-down form. The famous firm of Holland and Holland is given credit for introducing the rook rifle in 1883, but many other makers large and small offered them, because there was a ready market.

Most smaller gun shops and less-well-known makers didn’t manufacture their products in the literal sense, not even shotguns. While some made the barrels, they bought actions and other parts or even complete guns from a large manufacturer (usually in Birmingham) selling to “the trade.” Using these wholesaled parts they assembled and stocked a gun to a customer’s order, marking it with their own name. This practice was well-established for shotguns and naturally was carried over by retailers who had customers who needed a rook rifle for leisure or for a keeper’s use.

Rook and rabbit rifles were light enough to be carried on a

walk in the country, accurate and powerful enough for small game, and often

very elegant in balance and fit-and-finish. Calibers included the .22 Long Rifle, but larger bores were made. Classic rook rifle calibers include the

.297/.230 Rook, the .300 Rook, the .300 Sherwood, and larger bores, up to .380,

all of them centerfire rounds. These little

guns were used to shoot rooks and the fantastically abundant rabbits found in

every country lane and on every estate: hence the name for this rather specialized

firearm. Some of the larger calibers

were used on roe deer but these guns are primarily for small game.

Rook and rabbit rifles were light enough to be carried on a

walk in the country, accurate and powerful enough for small game, and often

very elegant in balance and fit-and-finish. Calibers included the .22 Long Rifle, but larger bores were made. Classic rook rifle calibers include the

.297/.230 Rook, the .300 Rook, the .300 Sherwood, and larger bores, up to .380,

all of them centerfire rounds. These little

guns were used to shoot rooks and the fantastically abundant rabbits found in

every country lane and on every estate: hence the name for this rather specialized

firearm. Some of the larger calibers

were used on roe deer but these guns are primarily for small game.

The rook (Corvus

frugilegus) is a common British bird in the same genus as the North

American crow. Its principal diet is

earthworms, fruit, cereal grains, game bird eggs, and small mammals; unlike

American crows, rooks don’t principally feed on carrion. Rooks are sometimes regarded as an

agricultural pest because of the damage they do to crops and new plantings, and

because they eat the eggs and young of pheasants and grouse. Surprisingly to

Americans, young rooks who

The rook (Corvus

frugilegus) is a common British bird in the same genus as the North

American crow. Its principal diet is

earthworms, fruit, cereal grains, game bird eggs, and small mammals; unlike

American crows, rooks don’t principally feed on carrion. Rooks are sometimes regarded as an

agricultural pest because of the damage they do to crops and new plantings, and

because they eat the eggs and young of pheasants and grouse. Surprisingly to

Americans, young rooks who  have not yet begun to fly (“branchers”) are

considered edible. English cookbooks still contain recipes for rook pies: the

“Four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie” of the nursery rhyme is a reference

to eating rooks.

have not yet begun to fly (“branchers”) are

considered edible. English cookbooks still contain recipes for rook pies: the

“Four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie” of the nursery rhyme is a reference

to eating rooks.  Many a cottager or gamekeeper on a large estate ate rook pies

as a matter of course; rabbit was

another staple of the diet of the working man. A single shot rifle had no real disadvantage in this kind of shooting, as the

quarry was skittish and likely to flee as soon as a round was fired.

Many a cottager or gamekeeper on a large estate ate rook pies

as a matter of course; rabbit was

another staple of the diet of the working man. A single shot rifle had no real disadvantage in this kind of shooting, as the

quarry was skittish and likely to flee as soon as a round was fired.

One maker of quality shotguns who seems to have had an occasional customer wanting a rook rifle was William Richard Topham Leeson (1851-1934) first of Ashford in Kent, and later London. I am deeply indebted to Mr Adrian Macer of the UK, a collector and historian of Leeson’s guns, for information about him and his business, and also for alerting me to the existence of a Leeson-marked rook rifle made not in Birmingham, but in Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts!

The rifle in question is a Stevens “Favorite,” a design well

known to Americans. The Favorite was one

of the most successful products of the J. Stevens Arms & Tool Company. In various forms it sold well over a million units. The first version was introduced in 1889; and

later variations were made for at least a decade after Stevens was bought out

by Savage in 1920. Production of the

Favorite continued until 1930, but updated models were made by the present incarnation of the company, Savage Arms, in the

1970’s and 1990’s. The  older Favorites

are beautifully crafted, the very epitome of a lightweight small game gun. They were made in .22, .25, and .32 rimfire;

a slightly larger (and less commercially successful) large frame version (the

Model 44) was chambered in some centerfire calibers as well.

older Favorites

are beautifully crafted, the very epitome of a lightweight small game gun. They were made in .22, .25, and .32 rimfire;

a slightly larger (and less commercially successful) large frame version (the

Model 44) was chambered in some centerfire calibers as well.

Mr Macer displays on his web site what is undoubtedly is a Stevens Favorite, not a Model 44. It has some odd features, which led us to investigate how this quintessentially American rifle ended up being sold as a "rook rifle" in Leeson’s shop in Edwardian London. Researching the archives and the Internet, and old catalogues, we’ve uncovered some very interesting information.

Leeson had several addresses for his London business. Between 1904 and 1911, he had shops on Maddox Street, George Street, and Harewood Place, the last a prestigious location near Hanover Square. In 1906 he registered his firm as “W.R. Leeson, Ltd.,” and did business at that location until after World War One, when the post-war depression compelled a move to the company’s final address on Warwick Street, where the firm remained until closing in 1933.

While his principal trade was in high-grade shotguns, Leeson could and did supply customers with rook rifles. The Stevens Favorite on Mr Macer’s site is a beautifully finished example, with elegant case-coloring on the receiver, a half-octagon barrel, and Lyman tang rear and globe front sights. The barrel is marked with Leeson’s name and Maddox Street address, and is a pre-1920 rifle made by the J. Stevens Arms & Tool Company, what is usually called a “Model 1894” design. It is in a custom-made leather case, with accessories, and while it’s a .25 caliber rifle, is it not in .25 Stevens Rimfire. It is, rather, chambered for the centerfire .297/.230 Rook cartridge!

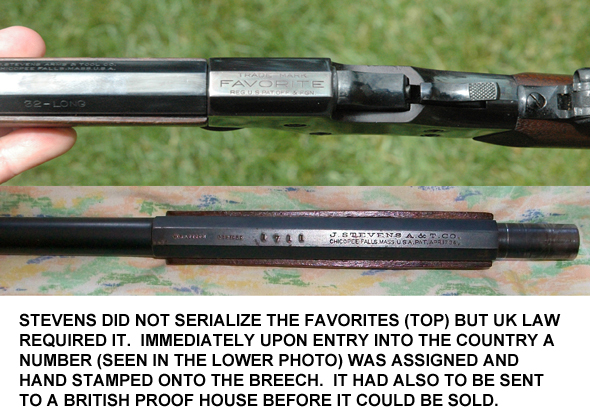

Guns coming into the UK are (and were) required to be

submitted for  proof before they could be sold, and this one bears London Proof

House markings indicating that this was done. It has a serial number, too, stamped into the top of the breech: this

was clearly a post-import marking because Favorites of that vintage aren’t

serialized, and the stamping is done rather crudely. Leeson added his own firm’s information.

proof before they could be sold, and this one bears London Proof

House markings indicating that this was done. It has a serial number, too, stamped into the top of the breech: this

was clearly a post-import marking because Favorites of that vintage aren’t

serialized, and the stamping is done rather crudely. Leeson added his own firm’s information.

The rifle is unquestionably a Favorite and not a Model 44. It would appear to be what Stevens’ catalog listed as a “#17,” ordinarily chambered for the .25 Stevens rimfire round; on the face of the receiver there is another marking “17 C,” which we think means “No. 17, C(enterfire).”

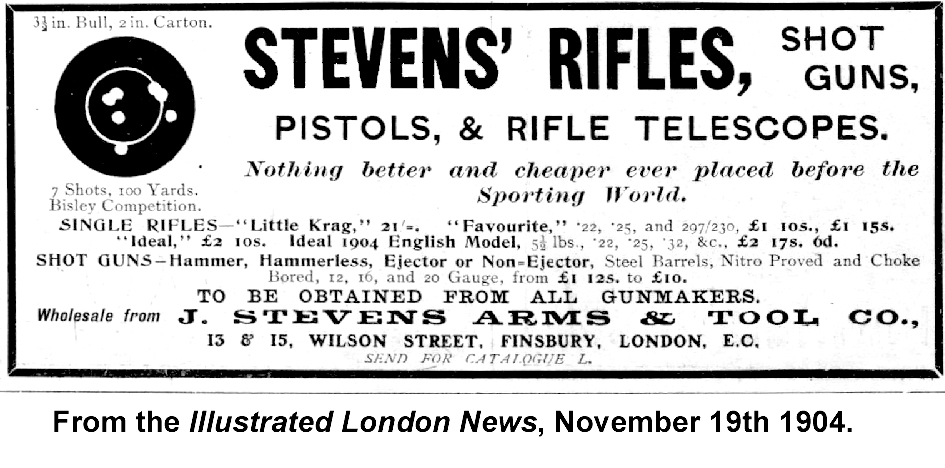

It would have been a trivial matter to rechamber the rifle to take the .297/.230 Rook round; and modifying the breechblock for centerfire ammunition would not have been difficult. Furthermore, Stevens did in fact have a business presence in the UK at the time. Their London agency was located less than a mile from Leeson’s shop. Although in its 1905 catalog for US sales, Stevens describes the Favorite as “…not made for centerfire cartridges…” the company clearly understood the British market.

The earliest advertisement for their guns I was able to find was in

the Illustrated London News for November 19th, 1904, which clearly states that the “Favourite”

(spelled in the British manner) was available in .297/.230 Rook, a classic centerfire round. In other words, the gun Leeson sold was an

“export model” made specifically for the UK market. Leeson’s shop records and those of the J.

Stevens Arms  & Tool Company are not accessible (and may no longer exist) so

it’s impossible to know for sure how many such “American rook rifles” may have

been produced, but they

& Tool Company are not accessible (and may no longer exist) so

it’s impossible to know for sure how many such “American rook rifles” may have

been produced, but they  cannot be very common.

cannot be very common.

The Leeson gun has several features that were available as special order from the factory, even for American customers. Among these are the tang rear sight and the folding Lyman front sight. These were likely requested by whomever placed the order through Leeson's shop.

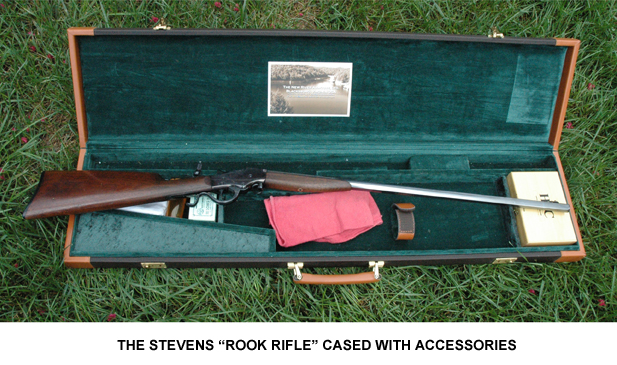

As is only right and proper, the Leeson gun was fitted into a custom-made hard-leather case, that is still in excellent condition. The case probably cost the owner as much as or more than the rifle did, but it's a beautiful example of leatherworking, and very suited to this diminutive game-getter. As was customary, although he didn't actually make the gun, Leeson added his trade label to the interior of the top lid.

Intrigued by the notion of as thoroughly “English” a style of gun as could be imagined being produced in Massachusetts, I took a look at my own Stevens Favorite. This is a “No. 18,” in .32 Rimfire, with a full octagon barrel, rather than the standard half-round, half octagon style. I had owned it for years and hunt small game with it. It was in very sound, shootable condition, but the original finish was completely worn off. I'd added an original tang sight, obtained from Classic Firearms & Parts in New Hampshire to complement the Beach patent folding front sight.

The .32 Rimfire’s ballistics are nearly identical to those of the .300 Rook. My rifle was well used when I bought it but was still tight, accurate, and had an excellent bore. I have a source of .32 Rimfire ammunition, so I decided to make my own version of an “American Rook Rifle.”

Depending on what references you read, Favorites were case colored (as the Leeson gun is) but also were available in blued finish. I shipped my rifle off for refinishing to Mr Dave Thomas, who runs Second Amendment Gun Repair in Pinehurst, Idaho. Dave is a master craftsman and returned it to me with a dazzling high-polish blue on the receiver and barrel, preserving all the markings.

Next item was the case. I’d acquired a brand-new hard-sided “motor case” at an auction very cheaply a few years before, with the original intention of using it for a shotgun, but I found that barrel set wouldn’t fit the case. However, the case was perfect for the Stevens. With a few added partitions and some green velvet to match the case lining, I had a custom-fitted case for my own “American Rook Rifle.” As a bit of personal vanity I added a “maker’s label” for my wholly-fictitious “New River Armoury.”

Having used my Favorite in the field, it’s easy for me to understand why rook rifles—wherever they were made—were so popular. Their light weight and perfect balance made it possible to carry one at the trail for long periods, their mild calibers didn’t disturb anyone in the vicinity, and minimized the danger of a bullet carrying too far, and the game pursued was well within the capabilities of these little guns.

The .25 and .32 Rimfire rounds were discontinued in 1942, with the USA’s entry into World War Two; production was never resumed. The improvement of the .22 Long rifle and flagging sales of the larger rimfires doomed them, but they were outstanding small game calibers, and there are many, many high-quality rifles languishing in closets for want of ammunition. A casual glance at any gun auction site will bring up dozens of Stevens “American rook rifles” for sale at low prices, usually in sound shooting condition. One can hope that some day, someone will do what’s needed to bring them out into the field once again, to delight another generation of recreational shooters.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |